Introduction: when the danger is in uniform

Most women are taught from childhood to look for the uniform if something goes wrong – to find a police officer, get to safety, and trust that badge. The latest revelations about the Metropolitan Police rip straight through that reassurance. A major vetting review has confirmed that more than 130 officers and staff, including two convicted serial rapists, were only in the force because basic checks were cut, rushed or actively overturned. One officer was initially rejected after an allegation of raping a child, only to be waved through by an internal panel partly set up to tackle “disproportionality” in recruitment.

Put bluntly, no wonder women are not safe in London when predators are allowed to wear the same uniform they are told to trust. This is not about one monster slipping through the net. It is about a system that lowered the net, looked the other way, and then acted shocked when the worst happened. The goal here is to cut through jargon and explain what has gone wrong, why it keeps happening, and what must actually change if Londoners – especially women – are going to feel safe again.

What the vetting review really found

The headlines about “two serial rapists” barely scratch the surface. The vetting review looked at recruitment and re‑vetting in the Met over roughly a decade, focusing particularly on the recruitment drive between 2019 and 2023. In that period, the Met was under pressure to hit ambitious government targets and bring in 4,557 new officers within three and a half years.

To hit those numbers, shortcuts were taken. The review found:

- 5,073 officers and staff had not been properly vetted, including thousands with no full reference checks or national security clearance.

- Of those, 131 went on to commit crimes or serious misconduct – everything from violence and drug use to racist abuse and sexual offending.

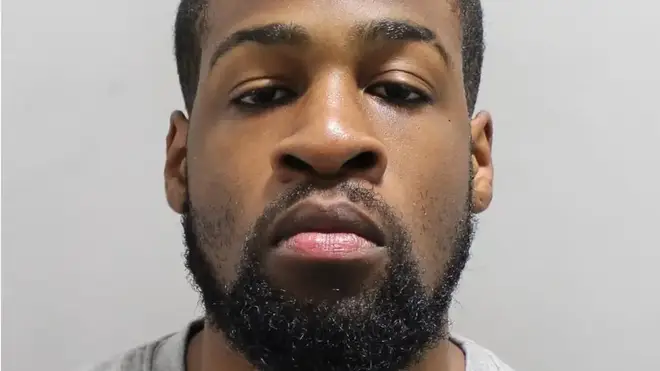

- Among them were two men who turned out to be serial rapists, including David Carrick, one of the worst sex offenders in modern British history.

This is what “deviations from policy” actually mean in human terms: women assaulted by men who should never have been given handcuffs and a warrant card; victims who trusted the uniform and discovered it belonged to their attacker. When you read those details, no wonder women are not safe in London stops sounding like rhetoric and starts sounding like a sober description.

The diversity panel, overturned refusals and hard questions

One of the most explosive findings concerns a now‑abolished internal vetting panel. Its stated aim was to tackle “disproportionality” – essentially to reduce perceived unfairness in vetting decisions affecting candidates from minority backgrounds. On paper, that sounds reasonable. In practice, it created a powerful loophole.

The panel reviewed 114 cases where applicants or staff had been refused vetting and overturned the refusal. Of those 114, 25 individuals went on to commit misconduct or be accused of criminal offences. One of those cases involved an officer whose original application was rejected because of an allegation that he had raped a child; the panel reversed the decision, and he later emerged as a serial rapist.

Two truths can exist at once here:

- Vetting systems can be biased and unfair, especially against people from certain communities.

- Weakening those systems without strengthening the underlying standards is reckless, especially in an organisation that hands people power, weapons and access to vulnerable citizens.

Diversity should never mean “lower the bar for basic safety”. Women and minority communities need officers who are both representative and safe. Building a police service that reflects London cannot come at the price of tolerating even one predator in uniform. When good intentions are used to justify bad vetting, everybody loses – and again, no wonder women are not safe in London when safeguarding gets tangled up in box‑ticking.

No wonder women are not safe in London

These vetting failures sit on top of what Baroness Louise Casey bluntly called a force that is failing women and children. Her 363‑page review found that:

- The Met has not protected women and girls from officers who commit domestic abuse or exploit their position for sexual gain.

- There is institutional sexism, racism and homophobia, and a culture where misconduct is too often minimised or brushed aside.

- Violence against women and girls is not treated with the prioritisation or resourcing given to other forms of “serious violence”.

Speak to women in London and you hear the same patterns. Some avoid reporting sexual harassment or assault because they worry they will not be believed – or worse, that they will be mocked. Others insist on having a friend present when speaking to police, or demand female officers where possible, simply because they do not feel comfortable alone with a man in that uniform anymore. These reactions are not the product of social media hysteria; they are rational responses to repeated revelations that some officers are themselves abusers.

So when people say no wonder women are not safe in London, they are not saying every officer is dangerous. They are saying the institution has repeatedly shown it cannot reliably keep dangerous men out, cannot consistently root them out once inside, and cannot yet guarantee that reporting a crime will not mean being re‑traumatised by the process.

Why the Met keeps hiring and protecting predators

It would be comforting to imagine that the problem starts and ends with vetting. It does not. Vetting is just the front door. Across multiple reports, the same deeper issues keep appearing:

- A culture of protecting your own – officers closing ranks, discouraging whistleblowers, and treating complaints as betrayal rather than a duty.

- A broken misconduct system – thousands of allegations, but very few resulting in dismissal, and some serious cases allowed to drag on for years.

- Years of austerity and target‑driven management – frontline safeguarding and local policing downgraded while numbers and headline targets took centre stage.

When a force is scrambling to meet recruitment quotas, the pressure is to get people in, not to ask awkward questions that might slow things down. When an officer is accused of misconduct, the instinct in a defensive culture can be to give them the benefit of every doubt rather than protect the public. Put those two instincts together and you get exactly what the vetting review describes: predators who slip through, and then stay, long after warning signs appear.

From a woman’s point of view, the message is harshly simple: the system has repeatedly prioritised numbers, appearances and internal comfort over your safety. Until that is reversed, no wonder women are not safe in London will continue to be more observation than exaggeration.

What real accountability and reform would look like

After every scandal, the Met talks about “learning lessons”. Women in London are entitled to ask: learning what, exactly, and by when? Real change means concrete measures that can be checked from the outside, not just new slogans. Based on the Casey review and the latest vetting report, genuine reform would include:

- Independent control of vetting and misconduct

Put vetting and serious misconduct decisions in the hands of a properly resourced, independent body with the power to override internal pressures. When someone with a serious allegation in their history is considered for a role with public power, the decision needs to be beyond internal politics. - Non‑negotiable standards and automatic triggers

Some behaviours – proven sexual assault, domestic abuse, exploitation of position for sex – should automatically end a policing career. No quiet moves, no “informal” outcomes. - Mandatory re‑vetting and data‑driven checks

Officers should not be “set and forget”. Regular re‑vetting, cross‑checking against new intelligence and complaints, and a system that flags patterns early could have prevented men like Carrick remaining in post for so long. - Disbanding toxic units and protecting whistleblowers

Baroness Casey singled out “dark corner” units where bad behaviour festers. Those need breaking up, and officers who report colleagues should be treated as doing their job, not betraying the family.

If these things do not happen, or only happen on paper, then the next scandal is not a risk – it is a timetable.

How women can try to protect themselves – and why they shouldn’t have to

The responsibility for fixing this mess lies with the Met, the Mayor and the Home Office, not with women. Still, many women understandably want practical steps they can take right now. Some sensible, if imperfect, options include:

- If you need to report a crime, take a trusted person with you to the station or meeting whenever you can.

- Ask for a female officer if that would make you more comfortable; you are allowed to say what you need.

- If an officer stops you in an isolated place and something feels off, you can call 999 to confirm they are legitimate and explain that you feel unsafe.

- Keep basic notes – dates, names, collar numbers – if an interaction feels wrong. That detail can matter later.

But it is crucial to repeat: the fact women are even having to think like this is itself a sign of institutional failure. In a city that worked properly, you would not have to game‑plan interactions with your own police. The long‑term answer is not better self‑defence by women; it is a police force that stops hiring and protecting the men they need protecting from.

Conclusion: trust has to be earned, not demanded

Trust in the Metropolitan Police is not some abstract constitutional issue; it is the difference between a woman feeling able to dial 999 and choosing not to. The vetting review and the Casey report both point to the same uncomfortable truth: for years, the Met has tolerated shortcuts, toxic culture and weak accountability that allowed dangerous men to flourish in its ranks. Against that record, no wonder women are not safe in London has become a widely shared verdict.

If policing by consent is going to mean anything, that consent has to be rebuilt from the ground up. That means independent vetting, real consequences for abusers in uniform, and leadership that welcomes scrutiny instead of dodging it. As a citizen, the most powerful things you can do are to stay informed, support those pushing for genuine reform, and refuse to let any force, however historic its name, treat your trust as automatic. A badge is supposed to be a promise. It is long past time the Met kept it.

FAQs

1. How many Met officers were affected by vetting failures?

A review found 5,073 officers and staff were not properly vetted; 131 of them went on to commit crimes or serious misconduct, including two convicted serial rapists.

2. Did a diversity panel really help a serial rapist into the Met?

An internal panel created to tackle “disproportionality” overturned 114 vetting refusals; 25 of those individuals later faced misconduct or alleged crimes, including one officer initially rejected after a child‑rape allegation.

3. What did the Casey review say about women’s safety?

Baroness Casey concluded the Met is failing women and children, has institutional sexism, and has allowed predators to flourish by not treating violence against women and girls as a true priority.

4. Are most Met officers dangerous?

Most officers are not rapists or abusers, but the system has clearly failed to keep a minority of dangerous men out, and has been too slow to remove them once inside, which damages trust in everyone.

5. What can the public do to push for change?

People can support independent oversight bodies, back campaigns from women’s and victims’ groups, press MPs and the Mayor to implement all Casey recommendations, and refuse to accept superficial “lessons learned” in place of measurable reform.

- Are Reform UK Just Another Establishment Party? The Uncomfortable Truth After 4 Decades Of Watching Politics

- England’s Towns Speak: A People‑Funded Rape Gang Inquiry Steps In Where the State Failed

- The Epstein Files, Mandelson and Why England Needs Self‑Governance Now

- London Councillor Paid While Living Abroad: No Wonder England’s Public Services Are in Such a Mess

- Rogue GOSH Surgeon Scandal: How Nearly 100 Children in England Were Harmed – And What Must Change Next

[…] “Why Women Don’t Feel Safe in London Anymore – And How the Met Police Failed Them” […]